Abstract

Introduction: Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most common disorder of porphyrin metabolism, resulting from a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD). It manifests with blistering cutaneous lesions on sun-exposed skin and is strongly associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Case Presentation: A 70-year-old Asian male with a history of successfully treated Hepatitis C presented with a several-month history of severe pruritus, skin fragility, blistering, and hyperpigmentation on sun-exposed areas. Diagnosis was supported by urinary porphyrin fractionation showing a classic pattern alongside elevated porphobilinogen (10.6 mg/24h) and delta-aminolevulinic acid (17.8 mg/24h) in the context of unequivocal clinical findings.

Treatment and Outcome: The patient was initiated on low-dose hydroxychloroquine (125 mg orally twice weekly). At six-week and three-month follow-ups, he reported a marked reduction in pruritus, complete cessation of new blister formation, and significant improvement in skin integrity.

Conclusion: This case underscores that PCT can manifest years after successful HCV treatment and highlights a pragmatic, cost-conscious diagnostic approach. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine proved to be a safe and highly effective therapy, leading to rapid and sustained clinical improvement.

Background

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), the most prevalent of the porphyrias, is an acquired or inherited photodermatosis caused by a deficiency in the hepatic enzyme uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) in the heme biosynthesis pathway [1]. This defect leads to the accumulation of hydrophilic, carboxylated porphyrins in the liver, plasma, and skin. Upon exposure to sunlight, these porphyrins generate reactive oxygen species, causing the characteristic cutaneous findings of photosensitivity, mechanical fragility, bullae, hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, and milia [2].

PCT is clinically classified into three subtypes. Type I (sporadic, ~80% of cases) and Type II (familial, autosomal dominant) are the most common. A major acquired risk factor for triggering sporadic PCT is underlying liver disease, with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection being the most significant association, implicated in up to 50-80% of cases in endemic areas [3]. Other common precipitants include alcohol abuse, estrogen therapy, HIV infection, and mutations in the HFE gene associated with hereditary hemochromatosis [4].

We present a case of PCT in a 70-year-old Asian male with a prior history of successfully treated HCV. This case is instructive for its demonstration of PCT onset years after HCV cure, the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by socioeconomic constraints, and the successful application of a low-cost, effective therapy [5].

Case Description

Presentation

A 70-year-old Asian male presented to the dermatology clinic with a four-month history of a progressive, intensely pruritic, and blistering rash. The eruption began on his anterior lower legs and later involved the dorsa of his hands and forearms. He reported significant skin fragility, noting that minor trauma would cause erosions and that blisters would rupture and crust over but heal slowly with residual pigmentary changes. He explicitly associated symptom exacerbation with sun exposure.

His medical history was significant for chronic Hepatitis C (genotype 1b), which had been successfully treated with a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen eight years prior, resulting in a sustained virologic response (SVR) [6]. He had no personal or family history of photosensitivity, blistering skin disorders, or porphyria. He denied any alcohol use, smoking, estrogen supplementation, or new medications. Review of systems was otherwise non-contributory.

Physical examination revealed skin findings predominantly on sun-exposed areas. The most severe involvement was on the anterior aspect of the left leg (Figure 1), demonstrating mechanical fragility with erosions, scattered tense vesicles and bullae, numerous milia, and mottled hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation. Milder similar findings were observed on the dorsa of both hands. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. The presentation on the anterior legs is classic, as these are often sun-exposed areas that receive significant UV radiation [7].

Diagnostic Assessment

Based on the classic clinical presentation and history of HCV, PCT was the primary diagnostic consideration. Initial laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, revealed microcytic anemia (Hemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, MCV 78.5 fL). Deficiencies in Vitamin B12 (108 pg/mL) and Vitamin D (18.1 ng/mL) were also noted. Liver function tests showed a mild, isolated elevation in alkaline phosphatase; alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were normal post-HCV treatment [6]. Serology confirmed prior hepatitis A and B exposure, and active hepatitis C infection (Anti-HCV positive). Testing for HFE gene mutations was not performed due to the patient's financial constraints and lack of insurance coverage [8].

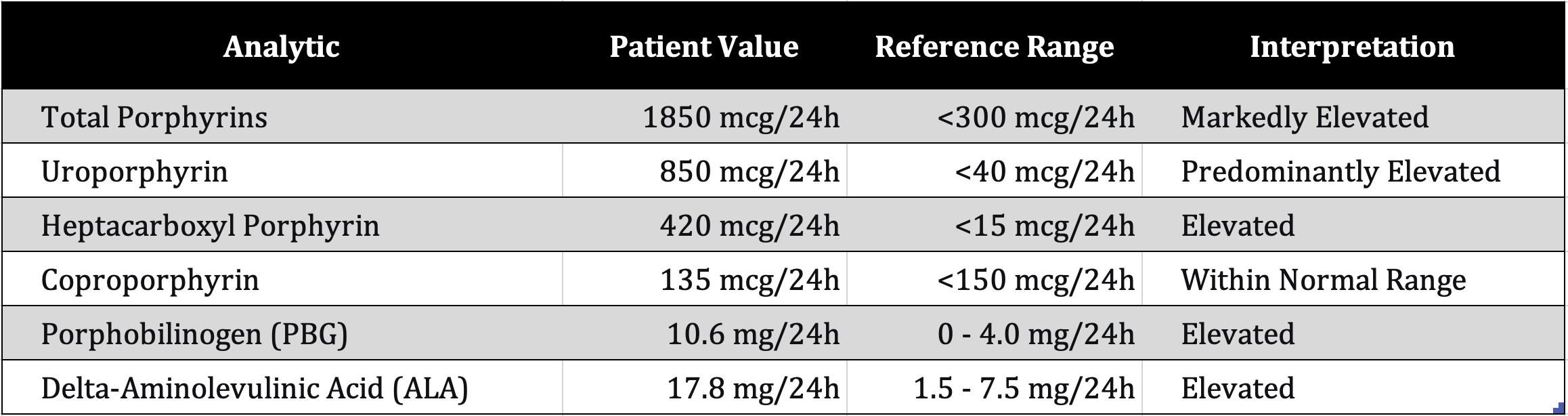

The diagnostic gold standard for PCT is urinary porphyrin chromatography, which typically shows a predominant elevation in uroporphyrin and heptacarboxyl porphyrin [9]. The results, which supported the diagnosis, are presented in Table 1.

Treatment and Outcome

The initial management involved patient education on strict photoprotection, including the use of sun-protective clothing and broad-spectrum sunscreens containing zinc oxide or titanium dioxide [10].

Given his history of treated HCV and financial constraints, pharmacological management with hydroxychloroquine was selected over serial phlebotomy. He was prescribed a low-dose regimen of hydroxychloroquine 125 mg orally twice weekly to minimize the risk of transaminitis [11].

The patient was followed up after six weeks and again at three months of therapy. He reported excellent tolerance of the medication with no adverse effects [12]. Subjectively, he noted complete resolution of pruritus, no new blister formation, and significant improvement in skin fragility. The existing erosions had healed, and the hyperpigmentation was beginning to fade. Based on this pronounced and sustained clinical improvement, the treatment was deemed successful.

Discussion

This case illustrates a typical presentation of sporadic PCT (Type I) unmasked by a history of HCV infection, even after its successful eradication [13]. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving HCV-induced subclinical liver injury and dysregulation of iron metabolism, which collectively inhibit UROD activity and predispose an individual to clinical disease [13, 14].

A central challenge in this case was navigating the diagnostic process amidst financial limitations. While a full urinary porphyrin profile is ideal [9], the combination of its results, elevated PBG and ALA, and unequivocal clinical features provided a sufficient and cost-effective basis for a confident diagnosis. It is important to clarify that PBG and ALA testing, while supportive, are not the diagnostic gold standard for PCT. The elevated PBG and ALA, while more characteristic of acute hepatic porphyrias [15], were interpreted cautiously in this unambiguous cutaneous context. This distinction is critical, as acute porphyrias present with neurovisceral crises, which were absent in our patient.

The treatment with low-dose hydroxychloroquine was highly effective. Hydroxychloroquine works by forming water-soluble complexes with excess porphyrins in the liver, facilitating their mobilization and renal excretion [10, 11]. The low-dose protocol (100-125 mg twice weekly) is now favored, as it significantly reduces the risk of acute hepatotoxicity compared to older, higher-dose regimens while demonstrating equal efficacy in achieving remission [11, 16].

Limitations

This case report has several limitations inherent to its setting and the patient's socioeconomic constraints. The diagnosis was made without a confirmatory skin biopsy, which was deferred due to cost. Assessment of key pathogenic factors was incomplete; HFE gene mutation analysis was not performed due to financial constraints and lack of insurance coverage. Finally, while follow-up shows sustained remission at three months, longer-term monitoring is needed to confirm durable remission and monitor for potential relapse [15, 17].

Conclusion

This case emphasizes that PCT is a crucial differential diagnosis for blistering eruptions in sun-exposed areas, particularly in patients with a history of liver disease such as HCV, even after successful treatment [5, 18]. It demonstrates that in settings with economic constraints, a pragmatic diagnostic approach is essential [5, 17]. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine (125 mg twice weekly) proved to be a safe, well-tolerated, and highly effective first-line therapy, leading to rapid and sustained clinical improvement [11, 16]. Continuous follow-up remains essential.

Tables and Figures

Figure 1. Cutaneous manifestations of porphyria cutanea tarda on the anterior left leg. The image shows the left lower limb with multiple hyperpigmented macules, atrophic scars, and crusted erosions along the shin. Notable features include excoriated papules, healed ulcerations, and extensive post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Characteristic findings are the darkly pigmented, shallow depressions indicating healed bullae, perifollicular hyperpigmentation, and scattered erosions on a background of atrophic skin, consistent with the profound photosensitivity and skin fragility of PCT.

Table 1. Urinary porphyrin fractionation and precursor results.

Details

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this work, the authors used generative artificial intelligence in order to edit, refine, and proofread the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Informed consent for treatment and publication was obtained from the patient. Conflicts of interest: All authors declare no conflicts. Financial relationships: All authors declare no financial relationships relevant to this work.

References

- 1

Elder GH, Bonkovsky HL, Phillips JD. Porphyria Cutanea Tarda and Related Disorders. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024.

- 2

Bissell DM, Anderson KE, Bonkovsky HL. Porphyria. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):862-872.

- 3

Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Pajares JM, Moreno-Otero R. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in porphyria cutanea tarda: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2003;39(4):620-627.

- 4

Singal AK. Porphyria cutanea tarda: recent update. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128(3):271-281.

- 5

Leaf RK, Dickey AK. Porphyria cutanea tarda: a unique iron-related disorder. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024;2024(1):450-456.

- 6

Bonkovsky HL, Rudnick SP, Ma CD, Overbey JR, Wang K, Faust D, Hallberg C, Hedstrom K, Naik H, Moghe A, Anderson KE. Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir Is Effective as Sole Treatment of Porphyria Cutanea Tarda with Chronic Hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2023 Jun;68(6):2738-2746.

- 7

Shah A, Killeen RB, Bhatt H. Porphyria cutanea tarda. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- 8

Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, Anderson KE. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):297-302.

- 9

Balwani M, Wang B, Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bissell DM, Bonkovsky HL, Phillips JD, Desnick RJ; Porphyrias Consortium of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. Acute hepatic porphyrias: Recommendations for evaluation and long-term management. Hepatology. 2017;66(4):1314-1322.

- 10

Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda--when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):735-745.

- 11

Singal AK, Kormos-Hallberg C, Lee C, Sadagoparamanujam VM, Grady JJ, Freeman DH Jr, Anderson KE. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is as effective as phlebotomy in treatment of patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Dec;10(12):1402-9.

- 12

Awad A, Nirenberg A, Sinclair R. Case Report: Treatment of porphyria cutanea tarda with low dose hydroxychloroquine. F1000Res. 2022 Aug 17;11:945.

- 13

Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int. 2012;32(6):880-895.

- 14

To-Figueras J. Association between hepatitis C virus and porphyria cutanea tarda. Mol Genet Metab. 2019 Nov;128(3):282-287.

- 15

Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Kushner JP, Pierach CA, Pimstone NR, Desnick RJ. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Mar 15;142(6):439-50.

- 16

Duan Y, Ni C, Huang L. Porphyria cutanea tarda treated with short-term high-dose hydroxychloroquine: a case report. AME Case Rep. 2022;6:19.

- 17

Sarkany RPE, Phillips JD. The clinical management of porphyria cutanea tarda: an update. Liver Int. 2024.

- 18

Chuang TY, Brashear R, Lewis C. Porphyria cutanea tarda and hepatitis C virus: a case-control study and meta-analysis of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Jul;41(1):31-6.