Abstract

Objective: Employers in service industries (e.g., healthcare) seek employees whose values align with serving others. To facilitate evaluation of these values, our objective was to develop and provide validity evidence for a simple tool for assessing people’s propensity to serve others and how serving others makes them feel.

Methods: We developed a 12-item tool, the New Helping Attitude Scale, and performed psychometric validity testing in two independent representative samples of the general adult U.S. population using a web-based platform.

Results: In a sample of 975 adults studied in three phases, we found that the 12 items of the New Helping Attitude Scale load on a single factor with all factor loadings >0.6 and good fit indices (Comparative Fit Index = 0.95; Tucker-Lewis Index = 0.94; Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual = 0.04). Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.92). In this report, we present normative data to aid in the interpretation of results.

Conclusion: The 12-item New Helping Attitude Scale is a simple, psychometrically sound, and reliable tool to assess people’s values related to serving others. Future research to determine its value in predicting job performance among employees in service industries such as healthcare is warranted.

Introduction

In service industries such as healthcare, organizations seek employees whose values align with the mission and values of the organization, e.g., a propensity to serve others. A simple tool for measuring prospective employees’ predisposition to serve others (versus serving oneself) may be useful in evaluating candidates for employment. Similarly, such a tool could also be helpful in vetting candidates for education and training programs in healthcare and related industries.

More broadly, ample research has linked serving others with benefits for the one who serves, including better physical health (longer life), mental health (less depression), and emotional well-being (more happiness) [1]. Future research testing the impact of other-serving behaviors on health may also benefit from such a tool.

Currently, there is no widely used assessment of other-serving orientation in healthcare and other service industries. The currently available measures are suboptimal because they include outdated language, have limited generalizability, and lack parsimony. A modernized, validated tool suitable for contemporary use in adult populations is needed [2].

Accordingly, our objective was to develop and provide evidence of validity for a simple tool for assessing people’s values related to serving others in a general population of U.S. adults. Because positive emotions from the experience of serving others are known to be a key determinant of sustaining one’s helping behaviors [1], we aimed to create a tool that assesses not only one’s propensity to serve others but also how it makes them feel, i.e., both action and emotion. Specifically, we sought to answer: (1) Can a more parsimonious scale be developed while maintaining psychometric properties? (2) Does the scale demonstrate validity and reliability in representative adult samples? (3) How are helping attitudes distributed in the general population?

Methods

This study was conducted from a post-positivist paradigm, employing quantitative methods to develop objective measures of helping attitudes. This was a cross-sectional web-based survey study conducted in three phases, spanning from 2022 (phases one and two) to 2024 (phase three). Because participants’ information was recorded anonymously, the Institutional Review Board at Cooper University Health Care (Research Protocol #21-118) deemed this study to be exempt from 45 Code of Federal Regulations requirements [3]. In addition to this exemption, we gave participants the following message prior to starting the survey: “Participating in this study is optional. By completing the survey, you are indicating your agreement to participate in the study.” This study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Our group is experienced in providing validity evidence for survey instruments, including the psychometric testing methodologies described below [4-6].

Recruitment of Participants

We recruited survey takers using SurveyMonkey Audience (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, California), a web-based crowdsourcing platform commonly used in social science and psychology research. Researchers recruit remotely located participants to perform discrete on-demand tasks such as completing research surveys through a web-based interface. This platform yields representative samples of target populations, in this case, the general U.S. adult population, by recruiting participants to match U.S. Census Bureau data on the basis of demographics. The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) age >18 years, (2) located in the U.S., and (3) acceptance of the invitation from SurveyMonkey Audience to participate in the research.

Phase One: Pilot Testing of Candidate Items

After a comprehensive literature review [1], we identified 20 candidate survey items that capture both action and emotion related to serving others. Specifically, we identified the 20 items in the Helping Attitude Scale, originally developed in 1988 by Professor Gary S. Nickell of Minnesota State University–Moorhead. It is a previously validated tool that assesses people’s propensity to serve others and how it makes them feel [7]. However, the tool has important limitations. First, there is validity evidence only in a convenience sample of college students rather than a general population, which limits generalizability. Second, it contains outdated language that limits its current relevance. Third, it has a high number (20) of items that are redundant to some extent, and thus it was unlikely to be the simplest, parsimonious tool. We address all three limitations with the current study.

We used an adaptation of the original 20 items (displayed in the Online Supplement, Supplementary Figure 1) as candidate items for our new measure. In addition to updating the language, we revised six items that were originally worded in a negative way (i.e., reverse-scored) to be worded in a positive way so that reverse scoring was unnecessary. Use of negatively worded (reverse) items is no longer recommended for psychometric studies because it does not achieve the intended effect of reducing response bias, is prone to miscomprehension, is problematic for factor analyses, and lowers internal consistency [8].

We administered the 20 candidate items to participants and performed exploratory factor analysis, which examines the factor structure and tests whether the results are explained by a single or multiple underlying constructs. Given that we aimed to develop a concise tool, we identified the candidate items with the strongest factor loadings on a single construct (e.g., uniquely loading on one factor). Then, to yield the most parsimonious set of items, we removed items with lower factor loadings, beginning with those below 0.40. We then sequentially removed lower loading items until fit indices (described below) stopped improving. The remaining items served as the final tool, the New Helping Attitude Scale, for which we provide validity evidence in Phase Two of this research.

Phase Two: Validity Evidence for the New Helping Attitude Scale

We studied the validity of the final tool in a second independent sample using confirmatory factor analysis with structural equation modeling and calculated standardized coefficients. Confirmatory factor analysis tests how correctly the hypothesized model, in this case a theorized single construct, matches the observed data. Given the non-normality of the data (i.e., ordinal data), we used the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-squared test for model goodness-of-fit. The Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-squared test is robust to nonnormality [8]. We tested comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) because these fit indices are optimal for large samples [9,10]. We defined good fit as CFI >0.95, TLI >0.95, and SRMR <0.08.11 We tested internal reliability using Cronbach’s α. We tested convergent validity with self-reported estimates of mean hours of volunteering per week.

We summed scores for each item to yield total scores, and we graphically represented the distribution as normative data to inform results interpretation. We tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We used Spearman correlation to test for convergent validity with reported weekly hours volunteering to help others.

Phase Three: Post-pandemic Repeat Validation

Because we wanted to make sure that the results remained robust in the post-pandemic era, we repeated the phase two methodology described above in another independent sample of adults in 2024. We also performed a post-hoc analysis, removing subjects with a perfect NHAS score of 60, to test if the correlation with self-reported estimates of volunteering hours changed substantially.

We used Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for all analyses.

Results

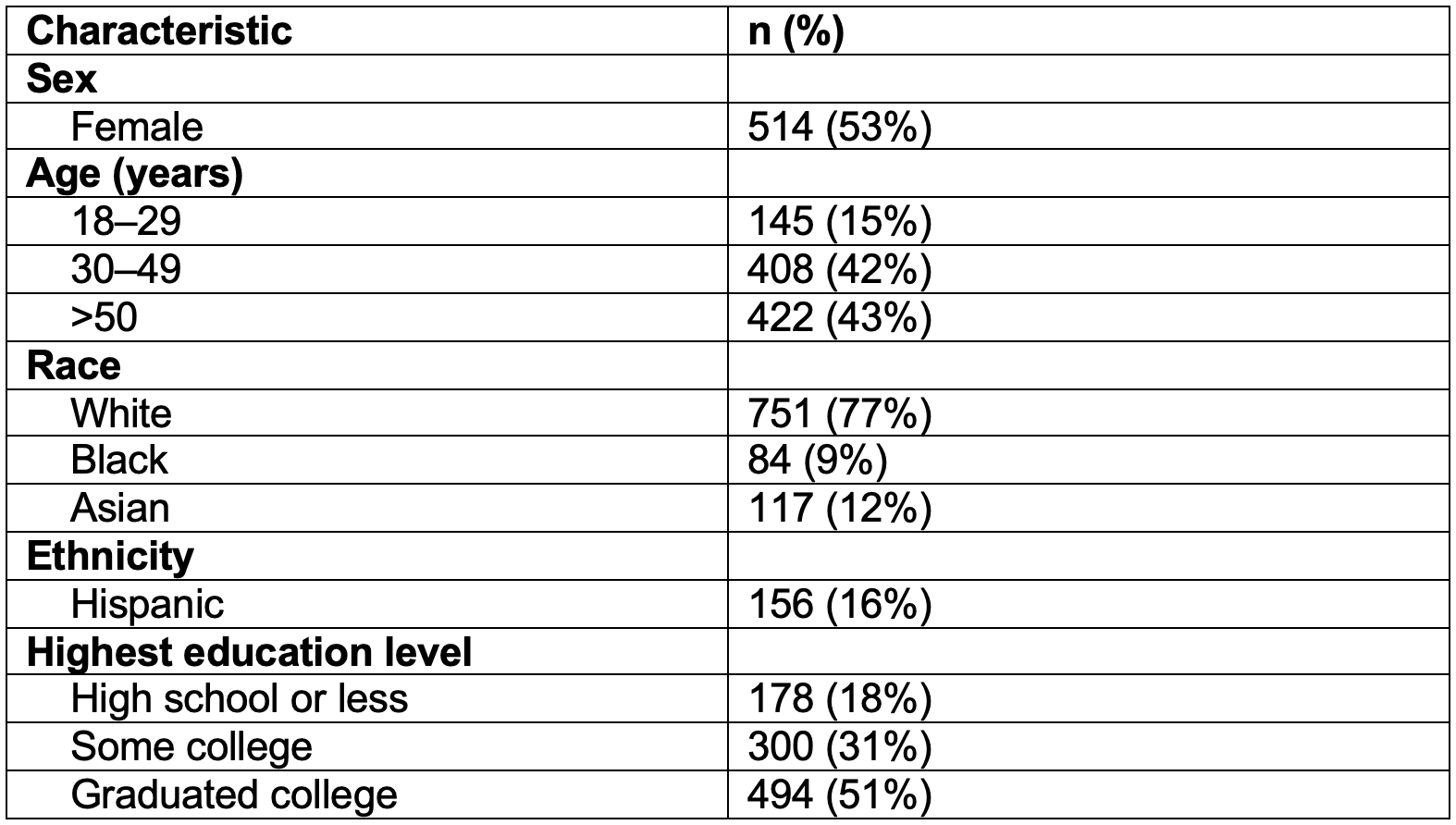

There were 975 total participants (phase one: 327; phase two: 310; phase three: 338). Self-reported demographics of participants are shown in Table 1.

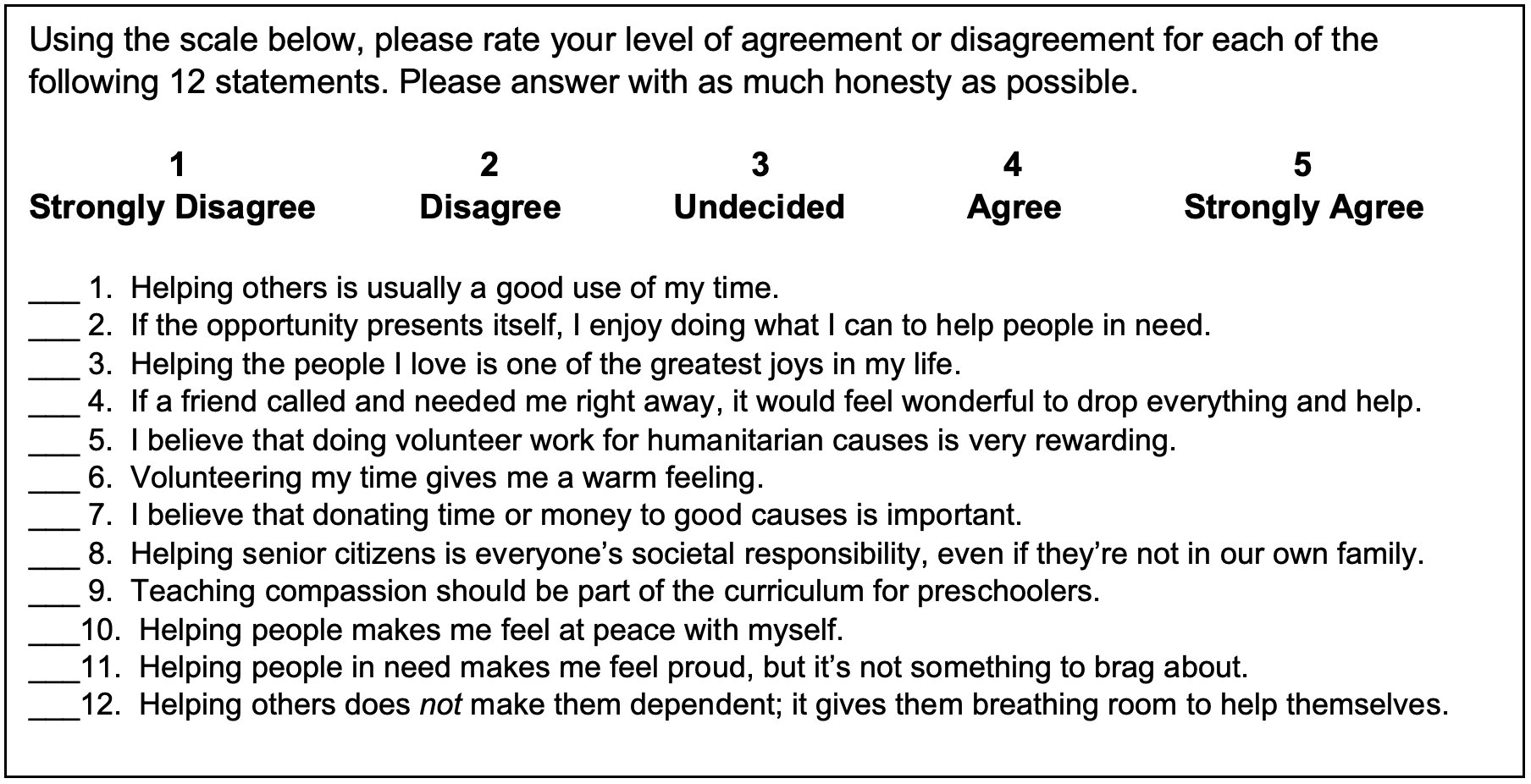

In phase one (n=327), exploratory factor analysis identified three factors: 16/20 items loaded on factor one, 3/20 items loaded on factor two, and one item loaded on factor three. After removing the four items related to factors two and three, we sequentially removed lower loading items until the fit indices stopped improving, which removed four more items. Thus, a 12-item tool (New Helping Attitude Scale, shown in Figure 1) was found to be the most parsimonious. Of note, the final 12 items had an almost perfect correlation with the full set of 20 candidate items (Spearman r = 0.96), supporting that the 8 items removed were redundant.

In phase two, studying validity evidence for the final 12-item tool in an independent sample (n=310), confirmatory factor analysis found that our final 12 items loaded well on a single construct (all factor loadings >0.60). The 12-item tool had good fit based on our a priori definitions (CFI 0.95; TLI 0.94; SRMR 0.04). While the Tucker-Lewis Index (0.94) fell marginally below our a priori threshold of 0.95, the other fit indices (CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04) met or exceeded criteria for good fit, and we interpret the overall model fit as acceptable. Internal reliability was excellent (Cronbach’s α=0.92). The correlation between the 12-item tool and self-reported estimates of weekly volunteering hours, i.e., convergent validity testing, was weaker than expected (r = 0.39).

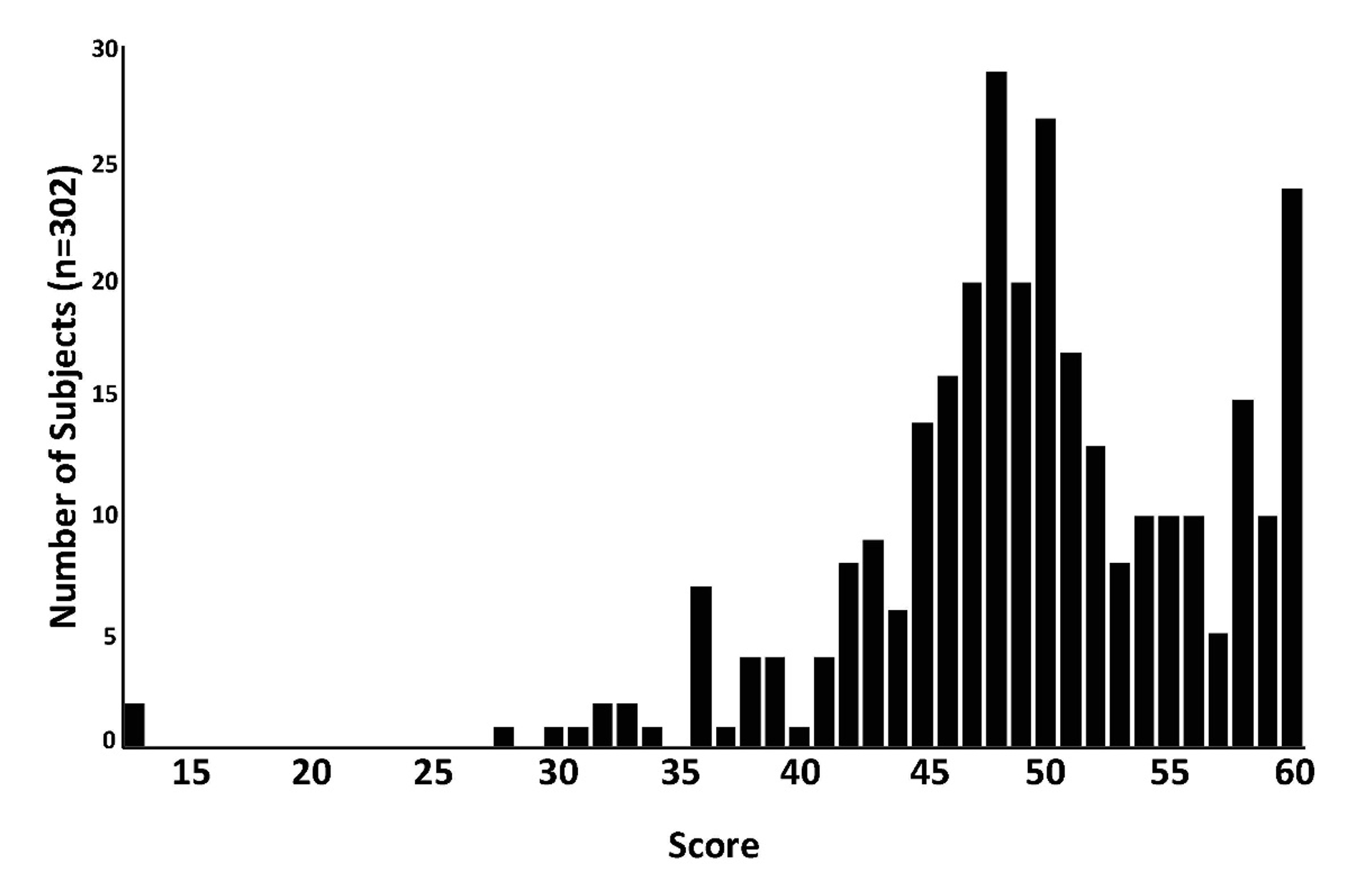

Normative data: Of the 310 surveys in phase two, 8 had one or more missing values, leaving 302 in the final sample displayed in Figure 2. Scores ranged from 12 (i.e., score of 1 for all 12 items) to 60 (i.e., score of 5 for all 12 items). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that the data were not normally distributed. The distribution appears to be bimodal, with a substantial proportion of scores clustered at 60, and the rest of the data centered between 45 and 50. The median score was 49 with an interquartile range of 46-54. The mean score was also 49, with a standard deviation of 7.

In phase three, studying validity evidence for the final 12-item tool in an independent sample (n=322 with complete responses), confirmatory factor analysis found that our final 12 items loaded well on a single construct (all factor loadings >0.60). The 12-item tool had good fit based on our a priori definitions (CFI 0.95; TLI 0.94; SRMR 0.04). Internal reliability was excellent (Cronbach’s α=0.93). Again, we found low correlation with self-reported estimates of weekly volunteering hours (r = 0.34). The distribution of scores in the phase three repeat validation was very similar (i.e., bimodal) to the results of phase two, as shown in the Online Supplement, Supplementary Figure 2. In the post-hoc analysis, removing subjects with a perfect NHAS score of 60, the correlation with self-reported estimates of volunteering hours remained low (r=0.29).

Discussion

In this study, we successfully developed and provided validity evidence for the New Helping Attitude Scale (NHAS), a modernized 12-item instrument for assessing altruistic attitudes in the general adult population. Our findings demonstrate strong psychometric properties across multiple independent samples, with excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α > 0.92) and robust single-factor structure and factor loadings. These results build upon and extend the original Helping Attitude Scale developed by Nickell [7], addressing its key limitations through updated language, elimination of reverse-scored items, and validation in representative adult samples rather than solely college students.

Situating Findings Within Existing Literature

Our work contributes to a growing body of literature on prosocial behavior assessment tools, addressing critical gaps in existing measures. While the original Helping Attitude Scale provided foundational evidence for measuring helping attitudes, it had notable limitations, including validation only in convenience samples of college students and outdated language that reduced contemporary relevance. The NHAS addresses these gaps while maintaining the theoretical foundation of assessing both behavioral propensity and emotional responses to helping—dimensions that align with established models of sustained prosocial behavior [12,13]. Research has consistently shown that positive emotions from helping behaviors predict sustained altruistic engagement [14], supporting our dual-focus approach.

The bimodal distribution observed in our normative data, with nearly 8% of respondents clustering at the maximum score of 60, warrants careful interpretation. This pattern may reflect several phenomena: (1) a genuine ceiling effect suggesting the scale may have limited discriminatory power among highly altruistic individuals, (2) social desirability bias inherent in self-reported altruism measures, or (3) potential satisficing behavior where some respondents selected all "5s" to complete the survey quickly. We conducted post-hoc analyses, removing participants who scored 60. The correlation with volunteering hours decreased minimally (r = 0.34 to r = 0.29) when these maximum scores were excluded. It is possible that both NHAS scores and self-reported volunteering hours may be subject to similar social desirability biases. In the absence of response time data (unavailable) or other indicators of satisficing behavior, we cannot definitively determine whether ceiling scores represent genuine high altruism or response bias.

Relationship to Healthcare Applications

While our study was conducted in the general U.S. adult population, we hypothesize that the NHAS may have particular relevance for healthcare and service industries. However, we acknowledge that direct evidence for utility in healthcare populations awaits future research. The theoretical alignment between the NHAS constructs and healthcare values is supported by literature demonstrating that healthcare workers who derive satisfaction from helping others show better job performance and lower burnout rates [15,16]. Research on compassion in healthcare settings suggests that assessment of service orientation may predict important outcomes [17]. Nevertheless, extrapolation from our general population findings to specific healthcare applications should be made cautiously, as healthcare professionals may demonstrate different response patterns or ceiling effects compared to the general population.

Methodological Strengths and Validity Evidence

Following contemporary validity frameworks that view validity as a continuum rather than a dichotomy [18,19], we provide multiple sources of validity evidence. Our content validity evidence derives from the adaptation of previously validated items with systematic updating for contemporary relevance. Structural validity evidence comes from our factor analyses demonstrating one-dimensionality across multiple samples. Internal consistency evidence supports reliability with Cronbach's α exceeding 0.92 in all samples. The consistency of findings across pre- and post-pandemic samples suggests temporal robustness of the scale's psychometric properties.

Limitations and Considerations

Several limitations warrant emphasis. First, our sampling methodology through SurveyMonkey Audience, while providing demographic representativeness, introduces potential biases. SurveyMonkey Audience does not provide traditional response rates because it uses a continuous recruitment model where participants who decline or abandon the survey are automatically replaced with demographically matched respondents until the target sample size is achieved. This approach ensures demographic representativeness but prevents calculation of a conventional response rate, which we acknowledge as a methodological limitation. The inability to assess response rate may introduce selection bias, as we cannot determine whether non-responders differ systematically from those who completed the survey.

Additionally, participants recruited through online platforms with incentives may differ from the general population in unmeasured ways, including technology access, education levels, or motivations for survey participation. This method may systematically exclude underrepresented groups without internet access or digital literacy, limiting generalizability [20].

Second, we acknowledge the absence of response-process validity evidence. Without cognitive interviews or think-aloud protocols, we cannot confirm that participants interpreted items as intended [21,22]. Future validation should incorporate these methodologies to ensure construct interpretation aligns with theoretical intentions.

Third, the modest correlation with self-reported volunteering hours (r = 0.34-0.39) represents weak relationships with other construct variables rather than external (convergent) validity concerns per se. This finding may reflect that formal volunteering captures only one manifestation of helping behavior, or that attitudes and behaviors are moderated by situational factors, including time, resources, and opportunities.

Fourth, we did not assess test-retest reliability, leaving temporal stability unknown. Given that helping attitudes might be trait-like or state-dependent, establishing stability over time would strengthen utility for selection or longitudinal research applications [23].

Fifth, external validity among samples that are more specific may be limited (e.g., if everyone in healthcare scores highly, it may not be able to distinguish). The scale was validated in the general population, and its discriminatory power in populations preselected for helping orientations remains unknown.

Finally, self-report measures of altruism face inherent challenges from social desirability bias. The social pressure to present oneself as helpful may inflate scores, particularly in contexts where prosocial values are emphasized [24]. Future research might explore methods to detect or control for socially desirable responding.

Future Directions

Several research priorities emerge from our findings. First, validation in specific populations, particularly healthcare workers and trainees, is essential before organizational application. Such studies should examine whether ceiling effects are more pronounced in service-oriented populations and whether the scale discriminates meaningfully among individuals already selected for helping professions.

Second, predictive validity studies linking NHAS scores to behavioral outcomes (such as job performance, patient satisfaction, or retention in healthcare roles) would provide crucial evidence for practical applications. Longitudinal designs tracking individuals from selection through performance would be particularly valuable.

Third, investigation of methods to address ceiling effects, such as item response theory approaches or development of additional challenging items, could enhance the scale's discriminatory power among highly altruistic individuals.

Finally, cross-cultural validation could examine whether the factor structure and psychometric properties generalize across different cultural contexts where helping behaviors may be differently conceptualized or valued.

Conclusions

The New Helping Attitude Scale provides a psychometrically sound measurement of altruistic attitudes in general adult populations, with strong internal consistency and structural validity evidence. While limitations exist and important validity evidence remains to be gathered, the NHAS represents a meaningful advancement over previous measures through its contemporary language, parsimony, and validation in representative samples. The scale captures not only one's propensity to serve others but also the positive emotions that flow from that experience, making helping behaviors more sustainable over time. Future research, particularly in healthcare populations where the scale may have the greatest application, will determine its utility for selection, training, and research purposes.

Tables and Figures

Table 1. Participant demographics. (Note: Values are self-reported by the user. Totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding and item nonresponse.)

Figure 1. The final 12 items of the New Helping Attitude Scale.

Figure 2. Distribution of scores for the New Helping Attitude Scale. The tool has 12 items, and each item has a 5-point Likert scale (1=least other-serving; 5=most other-serving), yielding a total score range of 12-60.

Details

Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosures

Drs. Trzeciak and Mazzarelli have co-authored books on the science of compassion and altruism. They donate author proceeds from sales of these books to charity (Cooper Foundation). They occasionally receive payments for speaking engagements on these topics. They have no relationships with commercial interests. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary Files

References

- 1

Trzeciak S, Mazzarelli A. Wonder Drug: 7 Scientifically Proven Ways That Serving Others Is the Best Medicine for Yourself. New York: St. Martin's Essentials 2022.

- 2

Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ 2015;4(5):252–53.

- 3

Protection of human subjects: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/regulatory-text/index.html accessed July 12, 2024.

- 4

Roberts BW, Roberts MB, Mazzarelli A, et al. Validation of a 5-Item Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion in Hospitals. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37(7):1697–703.

- 5

Roberts BW, Roberts MB, Yao J, et al. Development and Validation of a Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinical Compassion. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(5):e193976.

- 6

Sabapathi P, Roberts MB, Fuller BM, et al. Validation of a 5-item tool to measure patient assessment of clinician compassion in the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med 2019;19(1):63.

- 7

Nickell GS. The Helping Attitude Scale. 106th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. San Francisco, CA, 1998.

- 8

van Sonderen E, Sanderman R, Coyne JC. Ineffectiveness of reverse wording of questionnaire items: let's learn from cows in the rain. PLoS One 2013;8(7):e68967.

- 9

Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 2007;14(3):464–504.

- 10

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 2002;9(2):233–55.

- 11

Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press 2005.

- 12

Eisenberg N, Miller PA. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol Bull 1987;101(1):91–119.

- 13

Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Piliavin JA, et al. Prosocial behavior: multilevel perspectives. Annu Rev Psychol 2005;56:365–92.

- 14

Post SG. Altruism, happiness, and health: it's good to be good. Int J Behav Med 2005;12(2):66–77.

- 15

Gleichgerrcht E, Decety J. Empathy in clinical practice: how individual dispositions, gender, and experience moderate empathic concern, burnout, and emotional distress in physicians. PLoS One 2013;8(4):e61526.

- 16

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283(6):516–29.

- 17

Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:6.

- 18

Kane MT. Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. J Educ Meas 2013;50(1):1–73.

- 19

Messick S. Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons' responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol 1995;50(9):741–9.

- 20

Chandler J, Shapiro D. Conducting Clinical Research Using Crowdsourced Convenience Samples. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016;12:53–81.

- 21

Padilla JL, Benitez I. Validity evidence based on response processes. Psicothema 2014;26(1):136–44.

- 22

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications 2005.

- 23

Polit DF. Getting serious about test-retest reliability: a critique of retest research and some recommendations. Qual Life Res 2014;23(6):1713–20.

- 24

Paulhus DL. Measurement and control of response bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, eds. Measures of personality and social psychology attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press 1991:17–59.