Abstract

Background: Infective endocarditis (IE) remains associated with high morbidity and mortality despite advances in diagnosis and therapy. Biomarkers that integrate inflammatory and coagulation pathways may assist in risk stratification. The Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII), calculated as (platelet count × fibrinogen / leukocyte count), reflects the interaction between systemic inflammation and coagulation activity. This study evaluated the utility of SCII as a short-term prognostic marker in patients with IE.

Methods: In this prospective observational study, 26 consecutive adults diagnosed with IE at a tertiary care center in India were enrolled over a six-month period. SCII values were calculated from admission blood samples obtained prior to treatment initiation. Patients were followed throughout hospitalization, and mortality outcomes were recorded.

Results: The mean age of the cohort was 50.08 years, and 53.85% were male. Overall mortality during follow-up was 50% (13/26). Mean SCII was significantly higher in non-survivors than in survivors (176.2 ± 26.1 vs. 89.4 ± 20.7; p < 0.001). A strong association was observed between SCII and mortality (r = 0.77, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Elevated SCII at admission was significantly associated with short-term mortality in patients with IE. These findings suggest that SCII may serve as a useful adjunct for early risk stratification in IE. Larger studies with multivariate analyses are warranted to determine its independent predictive value and clinical applicability.

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the endocardial surface, typically involving the heart valves [1]. The pathophysiology of IE involves the formation of a vegetative growth on the heart valve, composed of bacteria and fibrin, which can lead to further complications such as septic emboli, valvular destruction, and systemic inflammation [2]. The diagnosis of IE is commonly based on the Modified Duke Criteria, which includes a combination of clinical findings, microbiologic evidence, and echocardiographic imaging [3]. IE can have severe outcomes, including heart failure, septic shock, and death, especially in cases complicated by embolic events [4]. Septic embolism occurs when infected material breaks off from the heart valves and travels through the bloodstream, causing obstruction and damage to distant organs.

The Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII) is a relatively new metric, calculated as the product of platelet count and fibrinogen levels, divided by white blood cell (WBC) count: SCII = (Platelet count × Fibrinogen) / WBC count [5].

This index has been proposed as a marker of systemic inflammation and coagulation status, which could be useful in predicting adverse outcomes in various clinical settings, including in patients with IE [6]. The formation of septic emboli in IE can be related to an inflammatory-coagulation imbalance, which may be reflected by alterations in SCII. Long-term prognosis of IE can help prevent chronic complications like heart failure [7]. Understanding the prognosis of a patient with IE, especially in the short term, can guide treatment strategies and patient management, particularly in terms of monitoring and preventing acute complications such as embolic events.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India over a six-month period (January–June 2025). All consecutive adult patients admitted with a diagnosis of infective endocarditis (IE) were included. The diagnosis of IE was confirmed according to the Modified Duke Criteria [8]. Patients with known co-existing inflammatory or autoimmune conditions were excluded to avoid confounding elevations in inflammatory markers. No retrospective data were used, and all data were collected prospectively at the bedside by the study investigators.

The sample size represents the total number of eligible patients admitted during the six-month study period. As this was a time-bound study, no additional sampling was performed beyond this window. Clinical data were recorded at admission, and patients were followed throughout hospitalization through direct bedside assessment by the study team.

Blood samples were collected at the time of admission, prior to initiation of antibiotic or anticoagulant therapy. Platelet count (×10^9/L), plasma fibrinogen (mg/dL), and total leukocyte count (×10^9/L) were measured using standardized automated assays in the hospital’s central laboratory, following routine internal quality controls. The Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII) was calculated for each patient using the admission values as per the formula: SCII = (Platelet count × Fibrinogen) / WBC count.

No data was missing for any included variable. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables as frequencies or percentages. Comparisons between survivors and non-survivors were performed using the independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate for the data distribution. Pearson correlation was initially used to explore relationships between SCII and clinical variables; however, due to the binary nature of mortality, logistic regression or ROC analysis is recommended for future work to better evaluate predictive ability. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

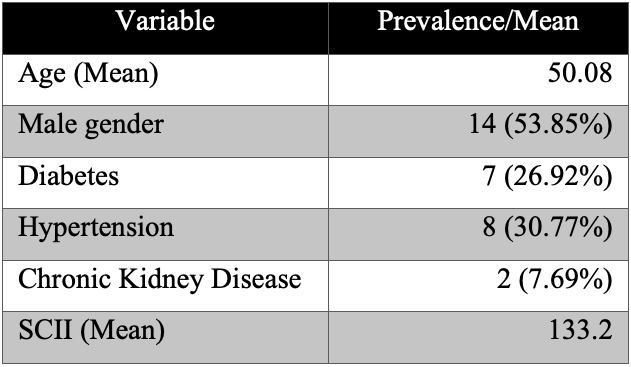

A total of 26 patients diagnosed with infective endocarditis were enrolled during the six-month study period. All patients were adults admitted to the tertiary care hospital. The mean age of the cohort was 50.08 years, and 14 (53.85%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes mellitus in 7 (26.9%), hypertension in 8 (30.8%), and chronic kidney disease in 2 (7.7%) patients. The mean Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII) for the entire cohort was 133.2. Demographic and baseline clinical data are summarized in Table 1.

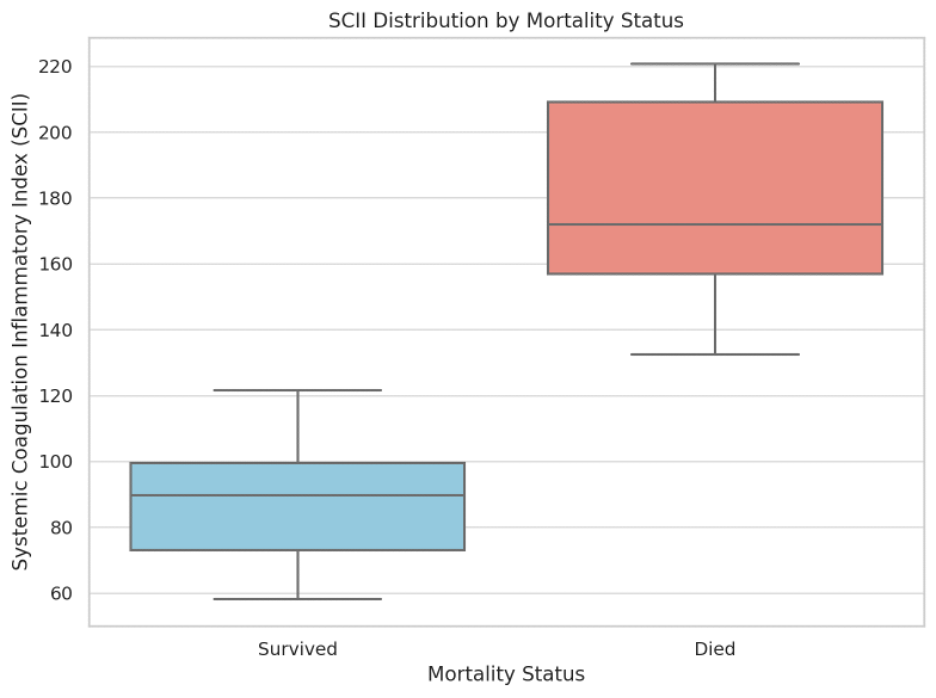

During the three-month follow-up period, 13 patients (50%) died. The mean SCII was significantly higher among non-survivors (176.2 ± 26.1) compared to survivors (89.4 ± 20.7, p < 0.001). The difference in SCII distribution between survivors and non-survivors is shown in Figure 1. The box plot depicts the median, interquartile range (IQR), and range for each group.

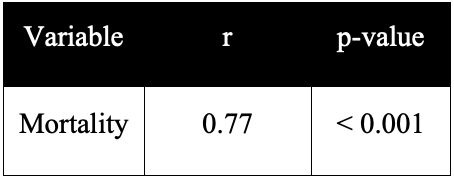

Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated a strong association between SCII and mortality (r = 0.77, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Given that mortality is a binary variable, this association should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Future studies incorporating logistic regression or receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses are warranted to evaluate the predictive accuracy of SCII for mortality risk in infective endocarditis

Discussion

Infective endocarditis (IE) continues to be a condition associated with substantial morbidity and mortality despite advances in diagnosis and treatment [9]. Identifying simple, reliable indicators that reflect disease severity or predict poor outcomes remains a clinical priority [10]. The present study prospectively evaluated the Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII) in patients with IE and found that higher SCII values at admission were significantly associated with mortality during short-term follow-up.

The SCII has been proposed as a potential prognostic marker in a variety of inflammatory conditions [11]. The SCII integrates platelet count, fibrinogen, and white blood cell count—three routinely measured parameters that together reflect the balance between systemic inflammation and coagulation. Previous studies have explored similar composite indices, such as the Systemic Immune–Inflammation Index (SIII), and reported their association with embolic and mortality outcomes in IE populations [12]. Our findings are consistent with these reports, supporting the concept that elevated inflammatory-coagulatory activity correlates with poorer outcomes in IE [13]. However, while the current study demonstrates an association between higher SCII and mortality, it does not establish SCII as an independent prognostic marker. Analyses such as multivariate logistic regression, ROC curve modeling, or Kaplan–Meier survival stratification would be required to demonstrate predictive performance and clinical utility [13].

Studies have also been conducted assessing its value in the risk of performing heart surgery [12]. The study’s results should therefore be interpreted as preliminary evidence suggesting that SCII may serve as a useful adjunct for early risk assessment in IE. The observed correlation provides a basis for hypothesis generation and for designing larger, multi-center studies to further evaluate the prognostic accuracy and threshold values of SCII.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, the small sample size (26 patients) limits statistical power and generalizability. This reflects the relatively low incidence of IE cases within the six-month study period rather than early termination or selective sampling. Second, only univariate analyses were performed; the potential influence of confounding variables such as comorbidities or causative organisms could not be excluded. Third, data on valve type (native vs. prosthetic), lesion location, and microbiologic etiology were not available, preventing more granular risk stratification. Finally, because SCII was calculated from a single admission sample, temporal variations in inflammatory or coagulation status could not be assessed. Despite these limitations, the prospective design, standardized laboratory measurement, and complete follow-up enhance the internal validity of the findings.

Conclusions

This study investigates the potential of the Systemic Coagulation–Inflammation Index (SCII) as a short-term prognostic marker in patients with infective endocarditis. Our findings suggest that SCII correlates with mortality outcomes and may serve as a valuable tool for early risk stratification. By identifying patients at higher risk of adverse events, SCII could help guide clinical decision-making and improve patient management strategies.

In conclusion, SCII presents a promising approach for prognostication in infective endocarditis. However, further research is needed to confirm these findings and explore their broader applicability in clinical settings.

Tables and Figures

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Table 2. Correlation between SCII and mortality in patients with infective endocarditis.

Figure 1. SCII distribution by mortality status (n = 13 survivors; n = 13 non-survivors).

Details

Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest or relevant disclosures.

Data Availability Statement

Full data of the study can be obtained on demand by contacting the corresponding author (surgeonsahasyaa@gmail.com).

References

- 1

Thuny F, Grisoli D, Cautela J, Riberi A, Raoult D, Habib G. Infective endocarditis: prevention, diagnosis, and management. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2014;30(9):1046-57.

- 2

Keynan Y, Rubinstein E. Pathophysiology of infective endocarditis. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2013;15(4):342-6.

- 3

Mahabadi AA, Mahmoud I, Dykun I, Totzeck M, Rath PM, Ruhparwar A, Buer J, Rassaf T. Diagnostic value of the modified Duke criteria in suspected infective endocarditis—The PRO-ENDOCARDITIS study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;104:556-61.

- 4

Kitts D, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Septic embolism complicating infective endocarditis. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1991;14(4):480-7.

- 5

Gelisimini EE, Biyobelirtec OI. A novel potential biomarker for predicting the development of septic embolism in patients with infective endocarditis: systemic coagulation inflammation index. Archives of the Romanian Society of Cardiology. 2024;52:36-43.

- 6

Delahaye F, Ecochard R, De Gevigney G, Barjhoux C, Malquarti V, Saradarian W, Delaye J. The long-term prognosis of infective endocarditis. European Heart Journal. 1995;16(Suppl B):48-53.

- 7

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler Jr VG, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000 Apr 1;30(4):633-8.

- 8

Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG Jr, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis–Prospective Cohort Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(5):463-73.

- 9

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. European Heart Journal. 2015;36(44):3075-128.

- 10

Agus HZ, Kahraman S, Arslan C, Yildirim C, Erturk M, Kalkan AK, Yildiz M. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts mortality in infective endocarditis. Journal of the Saudi Heart Association. 2020;32(1):58.

- 11

Erba PA, Conti U, Lazzeri E, Sollini M, Tascini C, Doria R, et al. Added value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the management of infective endocarditis. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology. 2012;19(3):546-57.

- 12

García-Cabrera E, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Almirante B, Ivanova-Georgieva R, Noureddine M, Plata A, et al. Neurological complications of infective endocarditis: risk factors, outcome, and impact of cardiac surgery: a multicenter observational study. Circulation. 2013;127(18):2272-84.

- 13

Cahill TJ, Baddour LM, Habib G, Hoen B, Salaun E, Pettersson GB, et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69(3):325-44.